According to an ancient southern Chinese form of black magic known as Gu a small poisonous creature similar to a worm could be grown in a pot and used to control a person’s mind.

Now a team of researchers in Shenzhen have created a robot worm that could enter the human body, move along blood vessels and hook up to the neurons.

“In a way it is similar to Gu,” said Xu Tiantian, a lead scientist for the project at the Shenzhen Institutes of Advanced Technology, Chinese Academy of Sciences.

“But our purpose is not developing a biological weapon. It’s the opposite,” she added.

In recent years, science labs around the world have produced many micro-bots but mostly they were only capable of performing some simple tasks.

But a series of videos released by the team alongside a study in Advanced Functional Materials earlier this month show that the tiny intelligent robots - which they dubbed iRobots - can hop over a hurdle, swim through a tube or squeeze through a gap half its body width.

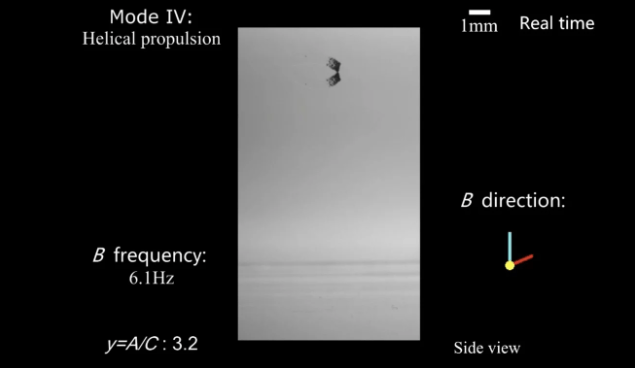

The 1mm by 3mm robotic worms are not powered by computer chips or batteries, but by an external magnetic field generator.

Changing the magnetic fields allows the researchers to twist the robot’s body in many different ways and achieve a wide range of movements such as crawling, swinging and rolling, according to their paper.

They can also squeeze through gaps by using infrared radiation to contract their bodies by more than a third.

The worm’s body is also capable of changing colour in different environments because it is made from a transparent, temperature-responsive hydrogel and the video shows that when added to a cup of water at room temperature they become almost invisible.

It also has a “head” made from a neodymium iron-boron magnet and a “tail” constructed from a special composite material.

Xu believes they will prove particularly useful for doctors in the future, for example by being injected into the body and delivering a package of drugs to a targeted area, for example a tumour.

This would limit the effect of the drug to the areas where it is needed and reduce the risk of side effects and the robot worm could exit the body once its task is complete.

The patient would need to lie in an MRI style machine that generates the magnetic field needed to control the robots during the procedure.

It could also be implanted into the brain because its high mobility and ability to transform means it can survive in this harsh environment where there are rapid blood flows and tiny blood vessels.

Currently, brain implants can only be inserted via a surgical procedure and have a limited capability to integrate with the neurons, which means they can only perform a few simple tasks.

But Xu said the new robots could “work as an implant for brain-computer interface” that would make it possible to communicate directly with a computer without needing a keyboard or even a screen.

She believes this would work by carrying a transmitter that converts external signals into an electric pulse and connect with brain cells to stimulate activities that are not possible using current technology.

Xu admitted that it may be possible to misuse the technology by turning it into a weapon, but said there were still some major barriers to making this effective.

For instance, the controller would need to build a powerful electric field generator with a long effective range to operate the robot worms.

It would also be very difficult to send the microbots to their designated locations without the co-operation of the person they are implanted into because they have to sit or lie down and stay perfectly still while they are moving through the body.

But improving the hardware may overcome these obstacles so Xu could not rule out the possibility the technology could be weaponised one day, but added: “We just hope that day will never come.”

This article was first published in South China Morning Post.