Monsanto expected thousands of farmers to complain about its new weed killer drifting and harming their crops when it launched the new dicamba-tolerant soybean and cotton cropping systems, documents presented in federal court on Wednesday show.

“We anticipated it might happen,” said Dr. Boyd Carey, regional agronomy lead at Bayer Crop Science, which bought Monsanto in 2018.

Carey oversaw the claims process for Monsanto’s 2017 launch of the new herbicide.

Carey testified from 9 a.m. until 5 p.m. Wednesday in a trial of a civil lawsuit filed by Bader Farms, the largest peach farm in Missouri, against Bayer and BASF.

Bader Farms, which says it is no longer a sustainable business because off-target movement of dicamba harmed its orchards, alleges that the companies intentionally created the problem in order to increase profits.

Monsanto developed the new technology after an increasing number of weeds developed resistance to the herbicide glyphosate (also called Roundup).

The St. Louis-based agribusiness company developed new genetically modified soybean and cotton seeds to withstand being sprayed by dicamba. Dicamba was developed in the 1950s but was not widely used in growing season because of its propensity to unintentionally move from field to field. Many crops, including traditional soybeans, are extremely sensitive to and can be damaged by dicamba.

In addition to the seeds, Monsanto and BASF, the original maker of dicamba, developed new versions of the weed killer touted to be less volatile than previous versions designed to be sprayed on the crops.

Even with those new versions, Monsanto expected complaints, documents show.

In an October 2015 document, Monsanto projected that farmers would file thousands of complaints in each of the next five years.

At that time, Monsanto was projecting that its weed killer would be available for the 2016 growing season, but it was not approved by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) until the 2017 growing season.

Still, the complaint projection proved accurate.

Monsanto projected 2,765 complaints about dicamba in 2017. In fact, the company received 3,101 complaints, Carey testified.

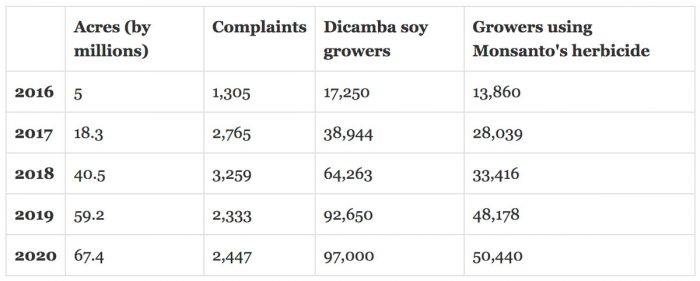

The projections for the overall number of dicamba-tolerant soybean acres planted were also accurate. Bayer has said that the acreage totals were about 20 million acres in 2017, 40 million acres in 2018 and 60 million acres in 2019.

In Oct. 2017, Kevin Bradley, a professor at the University of Missouri, projected that at least 3.6 million acres of soybeans were damaged across the Midwest and South in 2017. The complaints have continued in 2018 and 2019.

This chart, from a 2015 Monsanto Xtend soy projection entered into evidence, shows how many millions of acres and how many farmers would be growing dicamba-resistent soy between 2016 and 2020.

The number of complaints after the seeds were launched was significantly higher than in previous years.

Nationwide, in the five years preceding 2015, farmers never filed more than 40 claims about dicamba drifting, said Billy Randles, lead attorney for Bader Farms. However, that changed in 2015, when Monsanto released its new cotton seeds that could withstand being sprayed by dicamba.

Though dicamba was not approved for use on the crops, Monsanto felt it was worthwhile to release the new seeds because they were resistant to glyphosate and glufosinate, another herbicide that is sold by BASF under the brand name Liberty, Carey said.

Despite it not being legal to spray dicamba, some cotton farmers reportedly sprayed older versions of the herbicide, which drifted and harmed other farmers’ crops in 2015.

Monsanto and BASF were aware of the issue, Carey testified. However, Monsanto chose not to track drift complaints in 2015 or 2016. The company also had a policy not to investigate any complaints. Monsanto did not sell any versions of dicamba in 2015 or 2016. When Randles suggested Monsanto only started tracking claims because the EPA required it in 2017, Carey disagreed.

“We would have done that anyway,” he said.

In that time period and to this day, Monsanto and Bayer have a policy to not settle any claims of off-target movement, Carey said.

Dan Westberg, regional tech service manager at BASF, expressed concerns that the “widespread” illegal spraying would likely become “rampant” after Monsanto released its dicamba-tolerant soybeans in 2016. Westberg told officials that at a meeting in San Juan, Puerto Rico, on Feb. 11, 2016, Carey testified off his notes from the meeting.

In 2016, the alleged illegal spraying became so bad that the EPA issued a compliance advisory that said the Missouri Department of Agriculture had received 117 complaints of off-target movement.

The crops damaged included non-tolerant soybeans, as well as specialty crops like peaches. Bader had complained to Monsanto about his peaches being damaged by off-target movement of dicamba in 2015 and 2016.

Carey, who was in charge of developing the claims system for the launch of Monsanto’s Xtendimax with VaporGrip dicamba herbicide, testified that he wanted to investigate some claims just to see if he could learn anything but was advised not to.

In August 2016, the month of the advisory, Carey testified that he asked for a budget increase for the 2017 claims process from $2.4 million to $6.5 million.

The request included a projection that 20 percent of growers using the system would have inquiries about the system, including drift complaints. Randles raised questions about Monsanto’s handling of those inquiries.

A 2015 Mosanto document that discussed tools “available or under development” mentioned a dicamba inquiry form for the claims process once Xtendimax was launched. The document said the form was “developed to gather data that could defend Monsanto” and instructed field inspectors to look for symptoms other than dicamba, including environmental stress and other pesticide drift.

Carey said he was confident any 2015 form was not the final version of the form and that one of the best ways to investigate claims is to look at all possible options, including ruling out other potential causes.

“The most important thing is to visit the field,” Carey said. He said that’s the best way to understand the symptomology and eliminate other potential causes.

A 2016 incident management flow chart to help show how to process claims in 2017 showed that every claim that came in ended in “no settlement.” Carey said that is a long-standing company policy.

Carey testified that in 2017, Monsanto refused to visit any “driftee”—an internal term for those who received crop damage—who was not a customer. Inspectors were told to research the purchasing history to see if they were current Monsanto customers in “good standing,” or did not owe the company money.

Direct examination on Carey wrapped up Wednesday afternoon, and then Monsanto started its cross-examination, which took the rest of the day.

This article was originally published by the Midwest Center for Investigative Reporting, which is following this story on a daily basis. Visit their website to sign up for daily updates from the dicamba trial.

Top photo: Bill Bader, owner of Bader Farms, and his wife Denise pose in front of the Rush Hudson Limbaugh Sr. United States Courthouse in Cape Girardeau, Missouri, on Monday, Jan. 27, 2020. (Photo by Johnathan Hettinger/Midwest Center for Investigative Reporting)