Most Mondays my husband and I play a game. It’s called, “We don’t want to cook tonight; let’s get burritos.” And every week, lulled by low blood sugar and a bad case of the Monday’s, we play out our own version of a natural phenomenon. We show up to the burrito place, but there are no burritos to be had! Our taqueria doesn’t open until Tuesday. We are in the right place, but it is the wrong time. Will this barren wasteland, devoid of nutrition, cause us to perish?

An adult cod, Gadus morhua. Photo by August Linnman through Wikimedia Commons.

Match or Mismatch?

We, of course, can go somewhere else, but fish that have newly hatched in the ocean cannot. Yet they, too, need some good old-fashioned nutrition to survive and grow up to be valuable members of the ecosystem and fishery. In short, baby fish must be in the proper place at the same time as their food. While this may seem simple, sometimes the timing of prey and predator species don’t line up. This concept is called the Match-Mismatch Hypothesis, and every year we get to see if predator and prey match, or if they miss each other.

Of Cod and Calanus

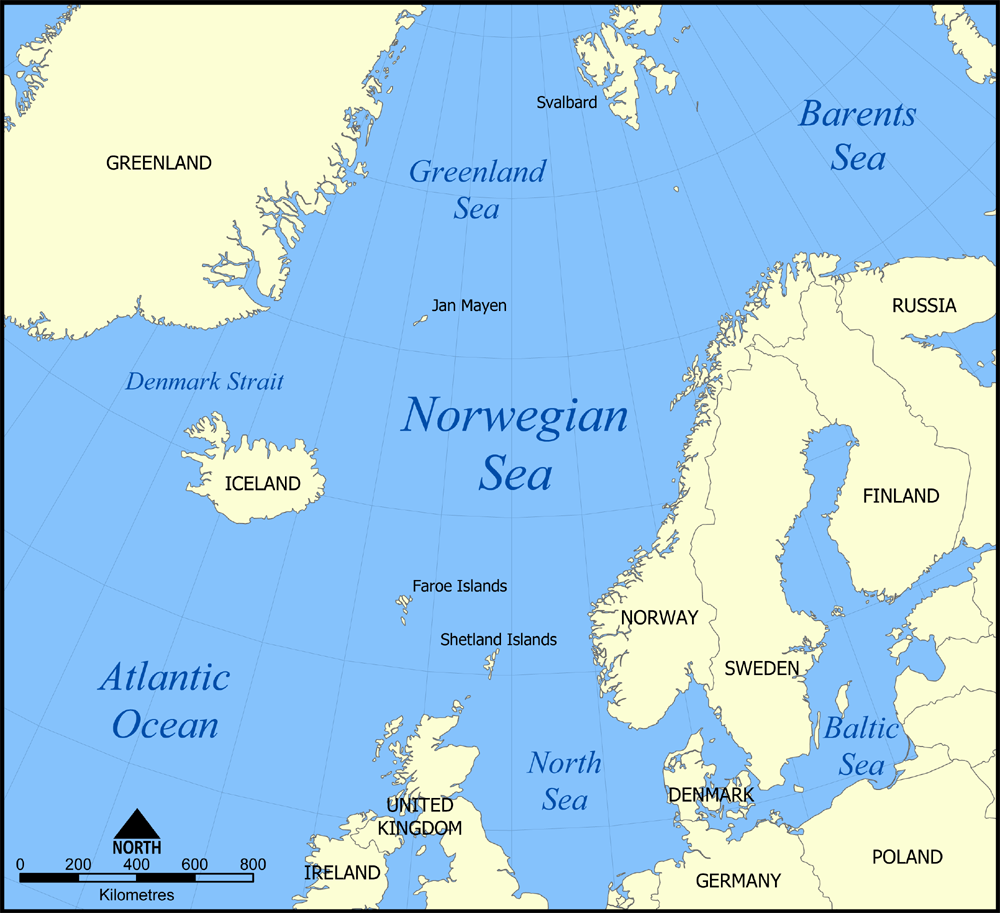

Although the Match-Mismatch Hypothesis seems fairly intuitive (if fish hatch when there is a lot of food, more fish will survive to adulthood), there have not been many studies that can prove this idea. In a recent article, researchers from Norway, USA, Denmark, and Russia teamed up to look at how the Match-Mismatch Hypothesis could be impacting the success of cod in the Norwegian-Barents Sea.

Cod is one of the most abundance species in the Arctic Norwegian-Barents Sea, where they spawn along the coast of Norway and eat the copepod Calanus finmarchicus. Copepods are small crustaceans, related to crabs and shrimp. What makes C. finmarchicus special is that it is particularly large and full of nutritious oils that can help a vulnerable cod larvae grow. According to the Match-Mismatch Hypothesis, newly hatched cod and C. finmarchicus (hereafter referred to as “the copepod”) have to be in the same place at the same time for cod to thrive.

A map of the Norwegian-Barents Sea region. Map from Wikimedia Commons.

To examine how copepod availability impacted cod survival, the researchers looked at a survey of newly-hatched cod and copepods in the Norwegian-Barents Sea from 1959-1992. First the researchers compared a number of methods for measuring the timing and availability of prey. Ultimately it was most useful to look at the overlap between timing and abundance of both the copepod and cod, or the predator-prey overlap. Scientists were then able to compare the predator-prey overlap to the number of cod that grew large enough to be a resource for the cod fishery, generally at 3 years old.

What they found

The researchers found that the overlap of the cod larvae between 11-15mm long (0.43-0.59 inches) and the copepods (their food) explained roughly 29% of the differences in how many cod had survived 3 years later. Think of it this way: if you were to try to predict how many cod would survive based on the predator-prey overlap alone, you would get the correct answer slightly less than once every three tries. This may seem small, but the researchers had to draw conclusions from the success of 3-year-old cod, not 1-year-old cod. A lot can happen in three years, even if the cod were initially aided by an abundance of food.

The availability of prey was not the only factor in cod survival. For example, a high number of the cod that hatched in 1970 were still alive three years later. This makes sense because a lot of cod hatched and there was ample food for them. This is like the taqueria on a Saturday; it’s open and everyone in town wants and gets burritos. However, in 1979, despite there being even more food available, the predator-prey overlap was low. There may have been a lot of prey, but few cod hatched that year. As a result, there weren’t a lot of adult cod three years later. 1979 is like the taqueria on a Tuesday: it’s open and there’s lots of food, but I’m not there to get the burritos.

The beautiful copepod Calanus finmarchicus, an important food source for cod. Photo by Terje van der Meeren.

Why does it matter?

The climate is changing, and as a result, so is animal behavior. Animals like cod and their prey rely on things like water temperature as signals to mate or move to a new location. Each year, they could mate at a slightly different time, meaning that any year cod could hatch to a sea full of food or to a barren wasteland. If we can measure how important this early stage is, we have a better chance of predicting how many cod there will be. With this, we can better manage cod fisheries and other economic issues.

Most importantly, in a world that is changing, it is important that we don’t base our predictions and studies on previous assumptions or patterns. Sometimes, our predictions and the reality could match, but what would it cost us if they were constantly mismatched?

I am a PhD student studying Biological Oceanography at the University of Rhode Island Graduate School of Oceanography. My interests are in food webs, ecology, and the interaction of humans and the ocean, whether that is in the form of fishing, pollution, climate change, or simply how we view the ocean. I am currently researching the decline of cancer crabs and lobsters in the Narragansett Bay.