If you are reading this, you are probably an amateur astronomer using a modern digital camera to capture the sky. An amateur astronomer is an amateur scientist. There are personal aptitudes that led you here, and for some people that aptitude leans more towards the artistic/qualitative side of astrophotography, and for others it leans more towards the analytical or quantitative side (and for some it’s both!).

Last month I talked about the qualitative value of “pretty pictures,” so this month I’ll give the more quantitative side of things equal time. If at some point you’re asking, how many more times you want to image M42 or the Horsehead Nebula, read on to see how to take your gear on a deeper exploration of the universe.

Richard S. Wright Jr.

First, let me establish a baseline principle. Your personal science projects do not have to change the world, be completely novel, or have value to anyone else to be real science. As long as you’re making observations and using those observations to better understand the world around you, you’re doing science. If you are repeating a 2,000-year-old experiment to demonstrate that the world is round, you are doing science. After all, a hallmark of science is reproducibility — repeating an experiment should give the same result.

Amateur scientists might occasionally make a groundbreaking observation or discovery, but we realize that this is a tremendous gift when it happens — not necessarily the status quo. Still, we sometimes play the lottery and hope we get lucky, do we not?

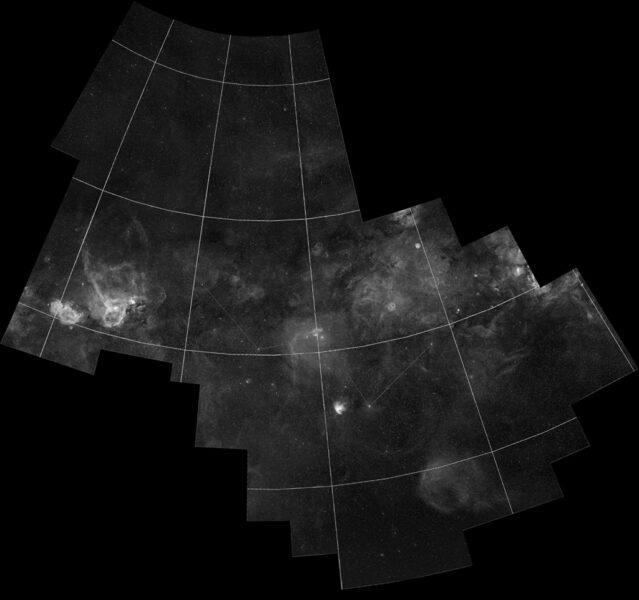

A great example of a collaboration between amateur astronomers who have pooled their resources and expertise is the MDW Hydrogen-Alpha Sky Survey. (Full disclosure: Two of the members are or were Sky & Telescope editors.)

These (advanced) amateurs have set out to survey the Northern Hemisphere sky with deep, high-resolution hydrogen-alpha images. I think it’s wonderful that someone just thought “such a thing as this ought to be.” They did something that no professional institutions had the funding, time, or interest to pursue. The imagery being produced is stunningly beautiful and has even revealed a previously unknown supernova remnant.

MDW Sky Survey

Another great example of an amateur scientist is the most prolific amateur supernova hunter: Tim Puckett. An amateur astronomer based in Georgia, Tim started his own supernova-hunting program in 1994. With the help of other collaborating amateurs, he has discovered hundreds of extra galactic supernovae. Supernova searches are highly automated today, but amateurs still contribute occasional discoveries.

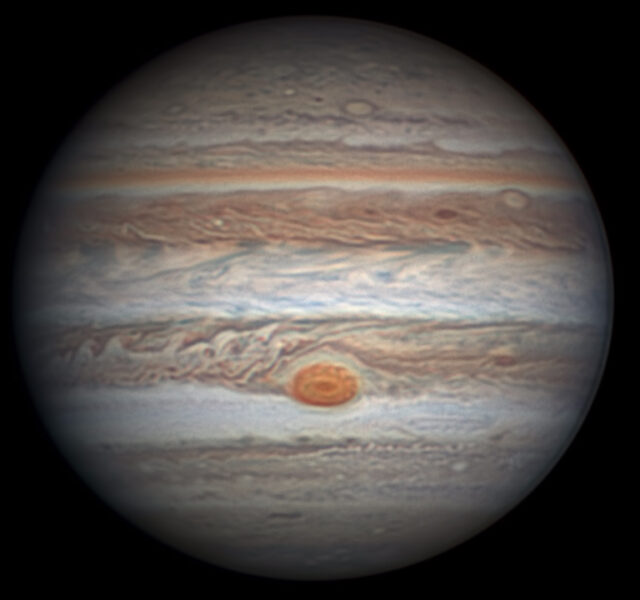

Christopher Go is also worthy of a highlight: a man who runs a furniture company by day and does planetary imaging by night. Christopher has made multiple discoveries, such as “Red Spot Jr.,” and coauthored a scientific paper in the journal Nature. Christopher is an excellent example of an amateur whose passion has blurred the lines between amateur and professional astronomy.

If you have some ideas for your own areas of research, you can also join the American Astronomical Society as an “Amateur Affiliate Member.” This membership class is for those who aren’t employed as astronomers but nevertheless may be working on research that they wish to report on, or who may take advantage of AAS resources for their work.

While you can certainly go and create your own scientific observing program, there are many organizations that have structured scientific programs an amateur can participate in. Participating in these programs can provide you with a framework to follow as well as training and guidance. Sometimes they even have mentoring programs.

Here are a couple of notable ones I recommend for astrophotographers.

AAVSO

Mike Simonsen

One of the best-known organizations for amateur/professional collaboration is the American Association of Variable Star Observers (AAVSO). In the AAVSO, amateurs learn the basics of photometry and how to make scientifically valid (from a quantitative point of view) observations to contribute to the work of professional astronomers.

A great example of this occurred in 2010, when amateur astronomer Barbara Harris made the discovery observations of a sudden outburst of the variable star U Scorpii. Barbara and other amateurs had enlisted in an AAVSO campaign to monitor this star for an eruption predicted by a professional astronomer. Barbara got up to let her dog out, flipped on her telescope, and and won the celestial lottery! Well, it wasn’t quite that simple (read the full story here). But just like in all forms of photography, “being there” is the most important thing.

If variable stars aren’t your thing, the AAVSO also has a fairly new exoplanet program where amateurs can participate in followup observations from data collected by the orbiting Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) telescope. I think making an observation that confirms the existence of a planet around another star would be a pretty exciting use for your backyard setup, and it can be done with an instrument with an aperture as small as 6 inches!

Solar System Studies

There are two organizations for amateur solar system studies: the Association of Lunar and Planetary Observers (ALPO) and the British Astronomical Association (BAA). Both have programs covering anything in the solar system. Solar and lunar programs, planetary imaging, comet studies, asteroid searches, the list goes on. For example, imagers can submit their images of sunspots to a repository that documents how these features evolve over time. Other examples are recording storms and weather events on Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. These observations contribute to our data pool and to our understanding of these processes. Taking part in these projects is within the reach of many amateur astronomers and imagers.

Christopher Go

Citizen science projects are a wonderful way to spend your time. Some people paint, some make Beer in their garage, and some of us study and document the heavens. Keep looking up and keep recording those ancient photons!