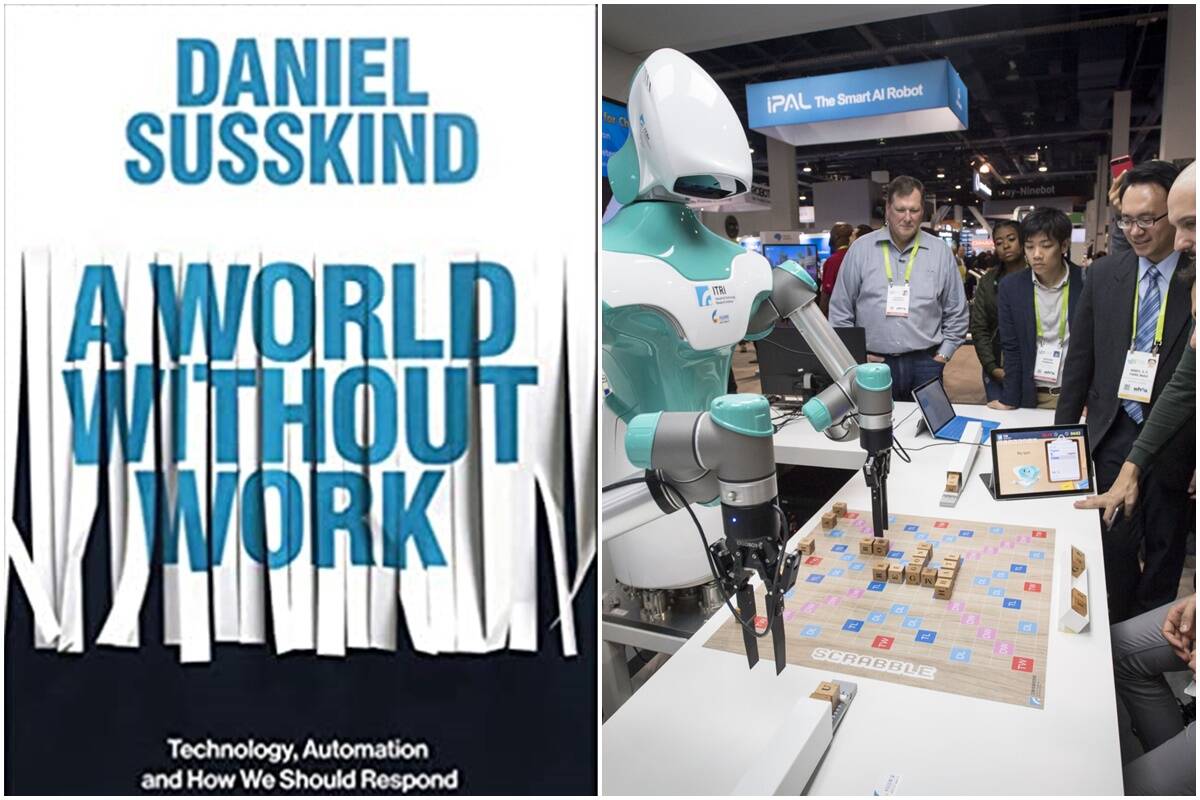

A file photo of an attendee playing a game of Scrabble against a robot at the Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas, Nevada, US (Bloomberg)

A file photo of an attendee playing a game of Scrabble against a robot at the Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas, Nevada, US (Bloomberg)

David Ricardo deliberated about the impact of technology on the nature of work much before Karl Marx’s writings. However, the first window of capitalism and the use of technology come from Marx. In a chapter in Grundrisse, titled “on Machines”, Marx details about the replacement of living labour with dead labour.

His deliberations on technology were not only limited to the impact on work, but the larger impact technological unemployment (a term coined much later by John Maynard Keynes) would have on society. Marx sees a dichotomy in the nature of machines, acting both as the cause of suppression of labour and its liberator. He says that as workers are liberated of the drudgery of human life, they would use their time to pursue more meaningful pursuits.

Keynes, writing nearly a century after Marx, is more alarmist. However, he reaches a similar conclusion. So, when France was deliberating a 28-hour work week—the proposal was rejected—Keynesians were smiling, as the famous economist had predicted a 15-hour work week by 2030. While we are still far away from a 15-hour work week, a decade is a long time. And, as Daniel Susskind remarks, the AI winter is coming.

I can go on with many more examples of economists with different leanings (from neo-classicals to Schumpeterian to Marxists and neo-Marxists) deliberating about the impact of technology on work, but that is what Daniel Susskind’s work is also about. Susskind, presently a Fellow in economics at Balliol College, Oxford, in his latest book A World Without Work, discusses both the evolution of technology and development of economic thought around technology’s evolution.

In the first half, Susskind sets the premise detailing the evolution of artificial intelligence and its comparison from past industrial revolutions that transformed the nature of work. The first four chapters are dedicated to explaining the role of technology and its impact on work, development of AI and the fallacy of human thought. The author time and again reiterates how we have repeatedly underestimated AI, and the ‘purists’ are proven wrong often. Terms like ALM hypothesis and task or skill-based view of job losses are presented in the four chapters to set the basis for Susskind’s theory of technological unemployment and the role of AI in coming years. Divided into three parts with four chapters each, the second part discusses the notion of task encroachment and the issue of technological unemployment in detail.

Susskind starts with a Keynesian metric of unemployment and then starts building upon it, while also deconstructing the Keynesian framework. The last chapter of the second part focuses on the issue of growing inequality related to technological unemployment and the growing difference between the haves and have-nots.

The third part is where Susskind presents his ideas about the oncoming revolution, and the impact it will have on education, society and the state. He discusses the role of the big state or big tech in controlling this revolution. And, expands on his ideas of what a society where there is little work would look like. The question, he says, is not about money but giving life a purpose. After two centuries of drudgery, capitalism has made us believe that this struggle is what gives life a meaning. He is sceptical about universal basic income but does not suggest an alternative to the scheme. The discussion about the means to provide support to the masses is not part of the basic theme also. There are examples of the aristocracy to define idleness, and examples of the building of civilisation, but there is no deliberation on whether everyone can be involved in such form of idleness or not.

The book is succinct and easy to understand; Susskind does not trap himself with over-explaining or under-emphasising concepts. But there are biases that emerge, which he moves past and does not address. The cost of technology and servicing is given little considerations in deciding whether technology will be adopted or not. While Susskind does give the example of car washes, where cheap labour displaced mechanical carwashes, he ignores the question of servicing the technology or ease of adoption. The business’ spending capacity also limits the Schumpeterian notion of creative destruction. In doing this, the argument on technology adoption becomes too simplistic. Self-driving cars are becoming a reality, but that may also mean the displacement of workers, not a replacement. An Uber driver may become obsolete in New York, but will still find work in smaller towns and cities where the cost of living is lower.

Similarly, considerations of cost are not paid heed to in the question of basic income. Even if one leaves aside the argument of who received the benefit, a larger force at play is the cost of goods. Will the government step in to keep the cost down, and if it does will it mean that the government will get into the business of production? Overall, Susskind provides an easy preview into the world of technology. You may not agree with him, but he certainly lends a different perspective.

BOOK DETAILS: A World Without Work: Technology, Automation and How We Should Respond by Daniel Susskind

Penguin Random House

Pp 336, Rs 999

Get live Stock Prices from BSE, NSE, US Market and latest NAV, portfolio of Mutual Funds, calculate your tax by Income Tax Calculator, know market’s Top Gainers, Top Losers & Best Equity Funds. Like us on Facebook and follow us on Twitter.

![]()

![]()