Any kind of photography, be it traditional photography or astrophotography, requires you to hone two skill sets. The first type are the skills you use to take the photo itself — mastery of your equipment and understanding light, composition, and framing.

The second skill set is what you need after you image, to process the data. While this used to be a mostly mechanical (or perhaps more accurately, chemical) process, today it is digital. We could arguably call this the analog and digital components of modern photography.

Richard S. Wright Jr.

The processing aspect of photography has developed an unfortunate stigma, due to a lack of understanding of how photography actually works. When attending workshops or discussing photography contests in online forums, I often hear “What comes out of the camera is all that should matter.” In the realm of both astrophotography and even traditional photography pursuits, “over-processing” is also a topic that will quickly assemble the social media villagers armed with metaphorical torches and pitchforks.

Richard S. Wright Jr.

I remember the days when I’d take a roll of film to the local drug store and drop it off for developing. Film had to be developed carefully to obtain good photos, but it was a mostly automated process by the time I came along. Nevertheless, the best places had a technician on hand to monitor and tweak the process. There were even specialized mail-order developing houses offering “superior” services, claiming better service than you could get at that little booth in the parking lot somewhere. Even so, an uncle of mine was an exceptional photographer, and he developed his film himself, in his own dark room at home.

Why the history lesson? Because almost nothing about this has changed today. What has changed is that the developing process is now digital rather than chemical, and the automation is small enough for you to hold in your hands. Today, the drug store and Photomat booths have been shrunk down and digitized, and reside onboard your smartphone and digital cameras.

Raw data off the camera’s sensor, just like film, has to be “developed” before you get that pretty picture. The world’s best photographers are just as skilled at image-processing as they are at operating their equipment. Computer algorithms analyze your image and adjust the brightness and color balance automagically just like the old film developing machine used to do. Even when a DSLR photographer shoots in RAW format, what they see in their favorite photo-editing software has already had numerous adjustments made to it.

Keep in mind, these adjustments are not actually changing the underlying data, only the presentation. With some skill and practice, photographers can then make further fine adjustments to obtain a final, dramatically improved image over what default processing would produce. Processing matters and is necessary regardless whether it’s the automatic processing that goes on in a digital camera’s onboard computer, or the more carefully guided processing performed in Photoshop or Lightroom by a talented photographer.

Richard S. Wright Jr.

In astrophotography, this division of labor is even more apparent and important. A dedicated CMOS or CCD astronomy camera doesn’t have the on-board computer that a modern digital camera (or even a smartphone) has. These cameras are controlled by an external computer, which runs software that permits little more than adjustments to the camera’s gain and exposure time. Then the software reads the truly raw data back from the camera. (Note: cameras don’t produce FITS files either, that requires software, too).

Many imagers just starting out, or even experienced ones who are transitioning to a dedicated astro-camera, are aghast when they see truly raw data for the very first time. I frequently hear the refrain, “For that kind of money . . .” as friends send me FIT files from an expensive camera I recommended. Truly raw data looks terrible most of the time.

There are also significant differences in how various astrophotography programs handle and display the data. “Images look worse in this software than when I open them in this other program,” folks will say. I’ll reply, “Send me the raw files.” The images always turn out to be identical, it’s just that the two programs are displaying it differently — auto-stretching routines vary wildly between packages.

Richard S. Wright Jr.

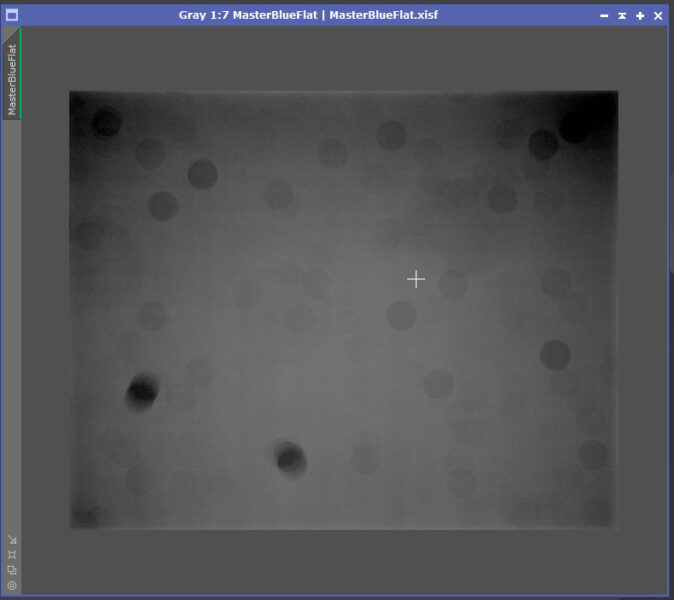

When a love of traditional photography leads to dipping one’s toes into the pool of astro-imaging, we now need to handle a number of things we had previously taken for granted. Often beginners, in a rush to apply all the tricks they learned in that PixInsight YouTube video, will skip over the one or more important steps of basic image calibration. The hurt they are dealing to themselves is that improperly calibrated camera data is much more difficult to process. Applying dark frames and properly recorded flat frames to remove thermal signal and dust or vignetting will make further processing much easier.

Richard S. Wright Jr.

The color sensitivity of the sensors is never the same as that of the human eye, and some color balance is always necessary to make things look more “natural.” Color data is often either far too red or far too green. In addition, a skilled photographer often makes final adjustments to things like saturation and sharpness to their photographs.

Some may call this cheating, but most cameras’ standard JPEG processing applies these changes, too; now you’re simply doing the job yourself. It’s like the difference between using a boxed cake mix and baking a cake from scratch. Some people are better cooks than others, but would you really accuse the latter of cheating because they didn’t use a prepackaged boxed mix like everyone else?