The everyday kindness of the back roads more than makes up for the acts of greed in the headlines.

— Charles Kuralt, late CBS News correspondent known for his in-depth reporting of society’s “back roads.”

Headlines are written to get attention. But sometimes they get the wrong attention for the wrong reasons, triggering the wrong reactions. Such is the case for this article on a recent study of Monarch butterfly population declines, written by Cornell University’s Alliance for Science, usually a solid, reputable source of unbiased scientific information:

Herbicide blamed for monarch butterfly population decline

The article’s author, Denmark-based journalist Justin Cremer, leads with an inflammatory paragraph:

A new study suggests that extensive agricultural use of glyphosate herbicide is to blame for the decades-long decline in North America’s monarch butterfly population.

Later, Cremer writes that the results instead “bolster the ‘milkweed limitation hypothesis.’ This theory points to the widespread use of glyphosate as the main cause of the population decline.”

But the paper, as Cremer later points out, claims nothing of the sort. The actual study, published in Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, and headed by University of Kansas emeritus professor (and Monarch expert) Orley Taylor and Iowa State University butterfly authority John Pleasants, instead refuted a stubborn hypothesis that the severe (more than 90 percent) Monarch population decline over the past few decades was due to losses during the butterfly’s southern migration. The paper supports another hypothesis that milkweed supply declines were the real culprit, among many other problems. Milkweed is used exclusively by the Monarchs for egg laying on their multi-generational migration from Mexico to Canada and back.

And what’s behind the milkweed decline? In short, land use changes fueled by politics (more on that below). But this fact hasn’t stopped anti-GMO groups from blaming the herbicide glyphosate, and by extension GM crops, for shrinking butterfly populations.

Activists target glyphosate

The world’s most-used weedkiller is a popular target of genetic engineering opponents because it’s used with herbicide-tolerant “Roundup Ready” corn and soybean, which now comprise more than 90 percent of all such crops grown in the United States. Previously, these groups blamed the GM plants themselves for milkweed and Monarch declines. Conservation group Environmental Action summed up the activist case in a recent petition urging individual states to ban glyphosate:

WE NEED TO BAN ROUNDUP TO SAVE MONARCHS.

If we want to save the monarch migration, one of nature’s greatest phenomena, we need to stop the habitat destruction that’s been causing their numbers to plummet.

A great step that your state can take? Ban Roundup, the weed killer whose active ingredient, glyphosate, decimates the milkweed plant monarchs rely on to survive.

More recently, activist groups have called for home-improvement retailers Lowes and Home Depot to stop selling Roundup (and its generic equivalents) because of its alleged impact on butterflies. Not long after the paper and Alliance for Science story were published, groups like Friends of the Earth and CommonDreams called for the sales ban:

In their pleas, the groups also cited the World Health Organization’s (WHO) International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) 2015 monograph, which linked glyphosate to certain cancers (a conclusion refuted by every regulatory agency in the world, including the WHO itself), and promoted organic farming methods (which do not exclude pesticides).

Perhaps ironically, the few media groups that covered the paper got the story right, making the Alliance for Science report stand out even more. For example, the online magazine DownToEarth correctly noted:

The decline in the population of Monarch butterflies — the most common ones found in North America — did not occur due to an increase in deaths during migration, showed a recent study.

This ‘migration mortality’ hypothesis was not backed by data, said Chip Taylor, a co-author of the study …. Taylor is also the director of Monarch Watch, a volunteer-based citizen science organization that tracks the fall migration of the Monarch butterfly.

The organization found butterfly populations declined for [most of] the past two decades, with the numbers of monarchs measured at their overwintering sites in Mexico during 2013-14 at an all-time low, according to Taylor.

So, what’s really behind the milkweed decline?

This is where things get complicated. Taylor told the Genetic Literacy Project that once glyphosate became popular, years before the introduction of GM corn and soy in the mid-1990s, it did almost eliminate milkweed from farmland. But, he added, that effect ended around 2006. Taylor, his co-author Pleasants and others were more concerned in 2000 about the use of GM crops bred to express Bt (Bacillus thuringiensis) Cry toxin, which kills caterpillars, though recent research indicates these insect-resistant plants probably don’t pose a risk to butterflies.

In fact, research has shown recent resurgences of Monarch butterflies, though their populations still remain significantly lower than their peak, as the Genetic Literacy Project explains in its FAQ on Monarchs and pesticides:

According to the independent Illinois Butterfly Monitoring Network, the population in 2018 reached the highest levels of the past 25 years, and the fourth highest level since 1993. The number of butterflies heading south to Mexico may reach as many as 250 million over the 2018-19 winter. At its peak in the 1990s, the population reached an estimated 900 million.

Since 2006, corn and soy production have surged, partly due to overall demand but largely because of the 2007 Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS), signed by President George W. Bush, that encouraged the use of corn-based ethanol in gasoline. The RFS subsequently boosted corn production and, according to Taylor, led to 24 million acres of marginal land being converted to corn crop—more than three quarters of this land was grassland that probably once had milkweed. Commenting on the Alliance for Science article Taylor added,

The text shows there is a failure to understand that long-term trends in populations are based on long-term trends. The trend here is loss of habitat and not mortality during migration or at other times in the annual cycle.

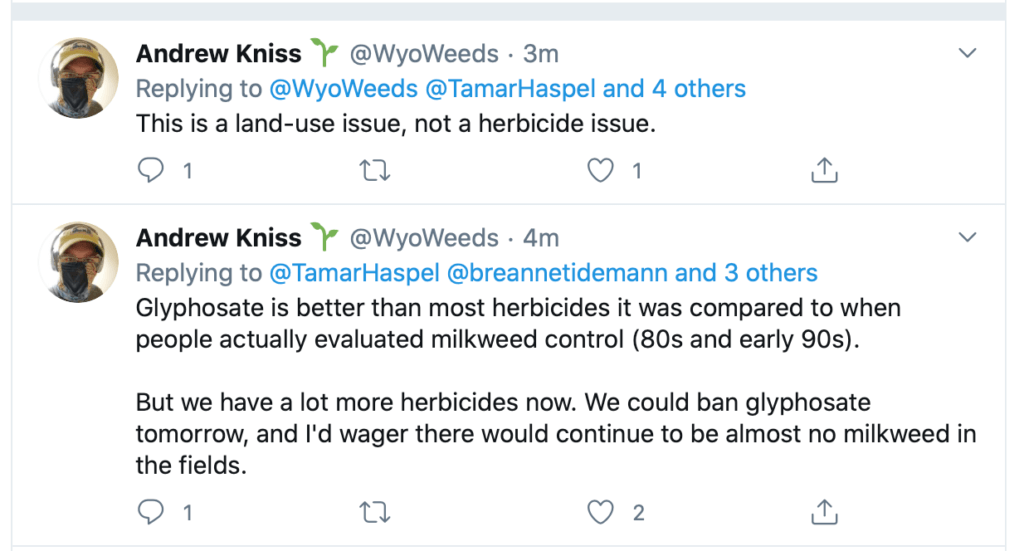

Andrew Kniss, weed scientist at the University of Wyoming, tweeted shortly after the Alliance for Science article ran. Echoing Taylor, he observed that this was an issue of milkweed habitat losses because of land use, not herbicides. And if not glyphosate, farmers would use something else:

And, in 2016, a Cornell University study reported that

In the face of scientific dogma that faults the population decline of monarch butterflies on a lack of milkweed, herbicides and genetically modified crops, a new Cornell University study casts wider blame: sparse autumnal nectar sources, weather and habitat fragmentation.

So, what kind of “everyday kindness” has been going on for the Monarch butterfly?

Monarch Watch and other groups have spent years advocating for accelerated planting of milkweed, especially along the migratory corridors through the US and Canadian Midwest. If farms can’t do it (or won’t, because milkweed is a weed and farming is a precarious business), other areas would work: public areas, highway medians, federal lands, parks, homes and schools. Taylor’s paper called specifically for replanting 1.4 million stems of milkweed to return to levels seen 40-50 years ago.

At Monarch Watch, “we now have over 30,000 registered sites with at least twice that number that have been created but not registered,” Taylor said. “There are plenty of opportunities to provide habitats for monarchs and pollinators in lots of marginal areas around farms and even in suburban and urban environments.”

Andrew Porterfield is a Contributing Correspondent to the Genetic Literacy Project. He is a writer and editor, and has worked with numerous academic institutions, companies and non-profits in the life sciences. BIO. Follow him on Twitter @AMPorterfield